Feminism

Pop Culture Monday: Lena Dunham’s Naked Body and Jodie Foster’s…Like, Gay?

It was a busy night yesterday for women in popular culture: there is definitely something interesting to say about the pairing of women and humour in Tina Fey and Amy Poehler hosting the Golden Globes, which I hope makes it to the feminist blogosphere before long (Any of you readers want to take a shot at it? Send me something and I’ll post it to 243 Conklin). Then there’s the two female stars who occupied much of the limelight at said awards show: Lena Dunham, whose Girls premiered its second season last night, and Jodie Foster’s ostensibly confusing–whether because of its content or delivery seems to be the debate in the social media sphere—pseudo-“coming-out”, pseudo-critique-of-celebrity-culture speech.

To recap and hopefully spark some discussion:

Via xojane: The Audacity of Lena Dunham, and Her Admirable Commitment to Making Us Look at Her Naked.

This piece captures well the problematic parameters of the interest, condescending humour, and critical obsession over the visibility of Lena Dunham’s naked body on Girls in the run-up to its second season premier.

In this case, we can’t stop talking about Dunham’s body explicitly because it is remarkable in its unremarkableness — Lena Dunham looks like what millions of women see in their mirrors every morning, women who see themselves and immediately catalog all the things they must “work on” in order to be passably acceptable enough to show their bodies, publicly or privately. By attacking Dunham, we are, to an extent, attacking ourselves.

And yes, after myself watching the premier last night, I am happy to confirm, without giving away any spoilers, that Dunham’s naked body was front and center more than once. It’s interesting to meditate on this piece’s invocation of Dunham’s “unremarkable” body. What, exactly, does “unremarkable” accomplish here? Is the aggregating logic of the statistical “normality” of a certain non-normative size of women’s bodies in America the best way to capture what is provocative about Dunham’s performance? There is also a lingering absence of whiteness in this conversation that would be interesting to mine further. The effects of capitalism, culture, labor and racism all shape–literally–the bodies of women.

Now, as for Jodie Foster…

I’ve been reading, mostly on Twitter, the back and forth arguments from a variety of people who feel that, variously, Foster’s speech was a lousy mess of a coming-out, that it was terrible but any coming-out is a “victory,” or that she was already out, making this poorly delivered speech irrelevant. I’m left wondering, though, if the larger lesson is not rather that coming-out is a somewhat out-of-date form of cultural-politics for mainstream celebrities? There’s an awkward speech and then there’s a controversial one, but I’m not sure this actually qualifies as all that interesting, politically.

Thoughts on any of this? Your contributions are invited and encouraged, as always.

Why Do So Many Women Leave Biology?

From Science Daily:

One common idea about why there are fewer women professors in the sciences than men is that women are less willing to work the long hours needed to succeed. Writing in the January Issue of BioScience, Shelley Adamo of Dalhousie University, Nova Scotia, Canada, rejects this argument. She points out that women physicians work longer hours than most scientists, under arguably more stressful conditions, but that this does not deter women from entering medicine.

Read the rest of the article here.

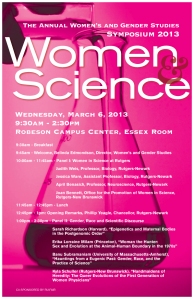

In the lead up to the Women’s and Gender Studies Annual Spring Colloquium “Women and Science,” we invite thoughts and responses to the issues raised in this article.

In Defense of Sluts | Yasmin Nair

While it is heartening to see an American President come even close to expressing what could effectively be translated as support for abortion rights, I have to wonder: What, pray tell, if Fluke is indeed a slut?

Read the full post here: In Defense of Sluts | Yasmin Nair.

Thoughts? Comments?

Event: Women’s History Film Festival

Of the Spirit

Women’s History Month film festival

March 3 – 5, 2011

All screenings will be at the Paul Robeson Student Center, Rutgers University – Newark Campus

350 Dr. Martin Luther King Boulevard, Newark, NJ 07102,

except for the 5:30 screening on March 3, 2011

*

Click links for further information

New Frontiers in Feminist Scholarship

Feminist scholarship is a tricky term. The qualifier “feminist” invokes provocative connotations, both good and bad, that can make discussions about feminism and feminist work treacherous terrain to navigate. Reflecting on this theme for the upcoming graduate panel for the 7th annual Women’s and Gender Studies Symposium at Rutgers, it is clear that what is new in feminist scholarship is incredibly broad and consuming. The idea of a frontier invokes stories of exploration. I think about US migration west, the hunt for adventure and fortune is the land that was just beyond the horizon. Perhaps that is the place to start for this topic: what is just beyond the horizon?

Newark, NJ is a fascinating place to be considering this question from. As one of the oldest cities in the country, there is a sense of excitement about change coming to the city. While it is true that Newark has been poised for this idea of renaissance since the rebellions of the late 1960s, I find that Newarkers are less concerned with the idea of ‘re-birth’ and more concerned with solutions that can blaze a new frontier for the post-industrial city. People I meet everyday are taking their passions for art, housing policy reform, women’s rights, etc. and asking what can be done differently? There is an ethos of being proactive, rather than reactive, which is a challenge that I believe resonates with the current situation of feminist scholarship.

Feminist scholarship was born as a reaction to a void. Something was missing in academia and, indeed, the world at large. Feminism, at its broadest interpretation, was about addressing those gaps and re-framing how we told our stories. Once addressing the incorporation of female voice into larger narratives of society and history, feminist studies took an outward turn. Taking this new way of thinking “to the streets,” so to speak, feminist scholarship opened into other disciplines and took-up new questions that pushed on the initial limitations of the field. While always drawing from the past, feminist methods and theories began encompassing more of critical scholarship permeating an array of fields and methods of study.

When I think of feminist scholarship, particularly in 2010, I wonder if we have not conquered the frontier. Have we arrived at the cliffs of Monterrey, California, looking out at the vast limitation of the Pacific Ocean, with all our accomplishments behind us? If everything can now be incorporated into a feminist perspective, has feminist scholarship, in a sense, lost its salience? The original fire and innovation that sparked a revolution in the academy and the public sphere? Where are the voids now?

To be quite honest, I feel that academics are thoroughly reflective and self-conscious of their progress and limitations within their respective worlds. To that end, my question (really my challenge), to feminist scholarship is less about meditating on what we can do next, but rather a call to action. The progress of women’s studies has been central to opening up new avenues and possibilities of identity for people. The extension into gender and sexuality studies is proof of this. Yet I wonder if we, as scholars, are making the necessary contact needed to create progress (dare I say revolution?). We need to be relentlessly asking the question, why does it matter? But beyond that, I think it is our responsibility to make it matter.

For me, the new frontier in feminist scholarship must be about extending beyond our limits both intellectually and physically. Taking our theories and conclusions and applying to the groups we study, the neighborhoods we live in, and the governments we participate in–the institutions and people we are responsible to. How does our research effect and change us? Does all this work, all these conversations, translate into progress for the communities we study? How do we assess the impact of our work? Who, beyond our peers, is our research in conversation with?

What is our responsibility to our research? What do we do for our work, not just what our work does for us. I think some of the perks of doing “research” is that is it safe, for the most part. It is safe because, unlike with personal relationships, our work cannot always talk back. One of the new frontiers in feminist scholarship, at least for me, is about interrogating what a reciprocal relationship between scholar and scholarship. The progress to be made will only happen in new contexts and environments–on the new horizons.

Where are these new spaces exactly? I think one place in particular is here, in the places we inhabit. Engaging with and inviting the public into our work in new ways, as well as about our work, will guide feminist scholarship into the new frontiers. Participation in communities beyond our own, outside the limits of our comfort zones, will expose us to new ideas and ways of thinking that can revolutionize–or at least significantly influence–the direction of the field.

I hope that the panelists, speakers, and performers that Rutgers will be hosting this upcoming week will lead to thoughtful discussions on how we will embark on a new journey into women’s, gender, and sexuality studies drawing from new voices, experiences, and publics that our work will encounter.

Monica Barra is a student in the American Studies doctoral program at Rutgers University in Newark. Her research explores the relationships between the built environment and its social communities through the intersections of urban arts production, cultural geography, sociology, and urban ethnography. She is currently working on projects in Los Angeles, California and Newark, New Jersey. She is the graduate research assistant for the Women’s and Gender Studies program.